1. bienvenida

- Desliza hacia la izquierda para pasa al siguiente audio / Swipe to the left to go to the next audio

¡Bienvenidos al increíble Castillo de Pedraza!

¡Pasen, vean, escuchen y disfruten de una feliz estancia en este maravilloso castillo! ¡Desde este momento puedes sentirte un gran señor noble medieval o una dama y princesa del castillo!

A lo largo del recorrido podrás ver unas flechas que puedes seguir para no perderte.

Aun así, si tienes algún problema para seguir el recorrido marcado o con los audios, siempre puedes acudir a la taquilla de entrada y con mucho gusto te ayudaremos.

Para empezar el recorrido sitúate en el centro del patio de la entrada, cerca de la taquilla. y pasa al siguiente audio.

Welcome

Welcome to the amazing Pedraza Castle!

Come in, see, listen and enjoy a happy stay in this wonderful castle! From this moment you can feel like a great medieval noble lord or a lady and princess of the castle!

Along the tour you will see some arrows that you can follow in order not to get lost.

However, if you have any problems following the marked route or with the audios, you can always go to the ticket office and we will be happy to help you.

To start the tour, place yourself in the center of the entrance courtyard, near the ticket office, and go to the next audio.

1A. El nombre de “Pedraza”

¿Por qué se llama Pedraza? Fácil. Pedraza es un pueblo muy antiguo que fue declarado lugar histórico en 1951. Su nombre viene del latín, de la palabra «petra», que significa «piedra» o «roca». Y esto tiene sentido porque el pueblo está construido sobre una gran roca, lo que lo ha hecho un lugar muy importante y fácil de defender desde hace siglos.

No se sabe exactamente cuándo empezaron a llamarlo Pedraza, pero este lugar ha existido desde antes de los romanos. Durante la Edad Media, el nombre ya estaba bien conocido porque el pueblo se convirtió en un centro importante de defensa y gobierno.

¿Sabías que Pedraza solo tiene una entrada y salida, una enorme puerta medieval que se cierra por la noche, como si fuera un castillo de cuento?

The Name “Pedraza”

Why is it called Pedraza? Easy. Pedraza is a very old town that was declared a historic site in 1951. Its name comes from Latin, from the word “petra,” which means “stone” or “rock.” And this makes sense because the town is built on a large rock, making it an important and easily defensible place for centuries.

It’s not exactly known when people started calling it Pedraza, but this place has existed since before the Romans. During the Middle Ages, the name was already well known because the town became an important center of defense and government.

Did you know?… Pedraza has only one entrance and exit, a huge medieval gate that closes at night, like something out of a fairy tale castle!

1B. La Construcción del Castillo y sus Propietarios

El primer castillo, de estilo románico, lo construyó en el siglo XIII Fernán García de Hita, que era un nombre importante de Castilla. Pero… las familias Herrera y Fernández de Velasco lo reconstruyeron en los siglos XV y XVI y lo convirtieron en el castillo que vemos hoy.

Estas dos familias son bastante importantes en cuanto a la historia del castillo, mira:

Los Herrera fueron los primeros en usar el castillo como una fortaleza para defender la región y más tarde, los Fernández de Velasco, lo convirtieron en un símbolo de poder y prestigio. Y es que los castillos pasaron de ser lugares de defensa a convertirse en residencias elegantes para nobles, o sea, los ricos.

¿pero por qué era Pedraza tan importante?

Pues porque muchos nobles ricos y comerciantes de lana merina (que era una lana que se exportaba a los Países Bajos para hacer tapices) se establecieron allí́. Por lo tanto…Pedraza era un centro de poder, economía y administración en el país. Vamos, un museo vivo de esos tiempos de esplendor. La cosa es que, con el paso del tiempo, las ovejas dejaron de tener

tanta importancia, los feudos desaparecieron y, por lo tanto, el castillo perdió́ su esplendor. Acabó siendo abandonado hasta que, en 1926, el pintor Ignacio Zuloaga lo compró por 13.000 pesetas (78€) y lo restauró, convirtiéndolo en su estudio de pintura y su hogar.

Sabias que… Uno de los eventos más conocidos de Pedraza es la “Noche de las Velas”, en julio. Durante esta noche, todas las luces eléctricas del pueblo se apagan y miles de velas iluminan las calles y plazas, creando un ambiente mágico.

The Construction of the Castle and Its Owners

The first castle, built in the Romanesque style, was constructed in the 13th century by Fernán García de Hita, an important name in Castile. But… the Herrera and Fernández de Velasco families rebuilt it in the 15th and 16th centuries, turning it into the castle we see today. These two families are quite important in the history of the castle. Check this out: The Herreras were the first to use the castle as a fortress to defend the region, and later, the Fernández de Velasco family turned it into a symbol of power and prestige. Castles went from being places of defense to becoming elegant residences for nobles, or in other words, the rich. Why was Pedraza so important? Well, because many wealthy nobles and merchants of merino wool (which was exported to the Netherlands to make tapestries) settled there. So… Pedraza was a center of power, economy, and administration in the country. It’s like a living museum of those times of splendor. But, over time, sheep farming lost its importance, the feudal system disappeared, and so the castle lost its splendor. It ended up being abandoned until 1926, when the painter Ignacio Zuloaga bought it for 13,000 pesetas (78 euros) and restored it, turning it into his painting studio and home.

Did you know?… One of the most famous events in Pedraza is the “Night of the Candles,” in July. During this night, all the electric lights in the town are turned off, and thousands of candles light up the streets and squares, creating a magical atmosphere.

1C. La Muralla

¿Cómo la construyeron?

Construyeron la muralla en el siglo XIII con piedra muy resistente, aunque han tenido que repararla varias veces para mantenerla en pie. Algunas de estas reconstrucciones las llevaron a cabo las familias Herrera y Velasco en los siglos XV y XVI ¿os acordáis no? las dos familias que fueron muy importantes para el castillo.

A lo largo de los años, ni el mal tiempo ni los ataques enemigos lograron destruir la muralla. Aunque, si miras de cerca, podrás ver las marcas de proyectiles antiguos, como piedras de catapultas, balas de cañón, y disparos de armas antiguas como mosquetes. Si te fijas bien, puedes intentar encontrar estas marcas en la fachada del castillo.

Recuerda que Durante la Guerra de la Independencia contra Napoleón, las tropas francesas invadieron gran parte de España, y muchas localidades fortificadas como Pedraza sufrieron daños.

Aún así, los proyectiles no fueron lo peor, el mayor daño que sufrió el castillo fue cuando lo abandonaron, y los vecinos se llevaron piedras y otros materiales para construir sus propias casas. Se cree que la torre del homenaje perdió unos cinco metros de altura y que en algunas partes de la muralla faltan hasta dos o tres metros de piedra.

Ahora dirígete a la cañonera que está situada justo enfrente del Portón de entrada y una vez allí, pasa al siguiente audio.

The Wall

To feel like you’re in the Middle Ages, you can climb the castle wall and carefully walk along the edge. From there, you get incredible views of a landscape that seems frozen in time, and you can also see the castle itself, so for a few moments, you can perfectly imagine what life was like in that medieval fortress.

And… how was it built?

The wall was built in the 13th century with very strong stone (though it has had to be repaired several times to keep it standing). Some of these reconstructions were carried out by the Herrera and Velasco families in the 15th and 16th centuries (remember? The two families that were very important to the castle…)

Over the years, neither bad weather nor enemy attacks managed to destroy the wall. However, if you look closely, you can see the marks of ancient projectiles, like stones from catapults, cannonballs, and shots from old weapons like muskets. If you look carefully, you can try to spot these marks on the castle’s facade.

Remember that during the War of Independence against Napoleon, French troops invaded much of Spain, and many fortified towns like Pedraza suffered damage.

Even so, projectiles were not the worst. The most significant damage the castle suffered was when it was abandoned, and locals took stones and other materials to build their own houses. It is believed that the keep lost about five meters in height, and in some parts of the wall, up to two or three meters of stone are missing.

Now head over to the cannon port that is located right in front of the entrance gate and once there, go to the next audio.

2. Cañonera

Aquí́ estamos frente a una parte súper importante de la defensa del castillo: la cañonera. Está estratégicamente colocada justo para apuntar directo a la puerta principal. Su trabajo era fácil: si los enemigos conseguían entrar por la puerta, desde aquí́ los defensores podían dispararles con un cañón.

Este tipo de defensas era común en los castillos y fortalezas de la época. Cada estaba diseñado para mantener alejados a los enemigos y proteger a la gente que vivía dentro del castillo.

La cañonera no es muy grande, por lo tanto, parece que aquí́ se usaba un cañón pequeño, llamado falconete. Este cañón era más fácil de mover y disparaba balas más pequeñas, pero suficientemente fuertes como para hacer bastante daño a cualquier enemigo que consiguiese entrar.

¿Sabías que… además de cañoneras y torres, muchos castillos medievales usaban trampas, como puertas levadizas y «matacanes» (que eran huecos en las murallas por donde se tiraban piedras o aceite caliente sobre los atacantes) para defenderse de los invasores.

Ahora dirígete al fondo del patio de entrada a la derecha, donde verás unas escaleras de bajada y pasa al siguiente audio.

Cannon Port

Here we are in front of a very important part of the castle’s defense: the cannon port. It’s strategically placed to aim directly at the main gate. Its job was simple: if enemies managed to enter through the gate, the defenders could shoot them with a cannon.

This type of defense was common in castles and fortresses of the time. Each was designed to keep enemies away and protect the people living inside the castle.

The cannon port isn’t very big, so it seems a small cannon, called a falconet, was used here. This cannon was easier to move and fired smaller balls, but strong enough to cause significant damage to any enemy that managed to get in.

Did you know?… In addition to cannon ports and towers, many medieval castles used traps, like drawbridges and “machicolations” (which were openings in the walls through which stones or hot oil were thrown on attackers) to defend against invaders.

Now head to the back of the entrance courtyard on the right, where you will see some stairs leading down and go to the next audio.

3. Puerta escapatoria

Al fondo de este patio de entrada, hay algo que, de primeras, parece que no es muy importante pero la realidad es que era clave en caso de ataque: una puerta secreta de escape.

Aunque el castillo de Pedraza estaba hecho para resistir ataques, los dueños también pensaban en la posibilidad de que los enemigos ganaran. Ahí́ es donde entraba en juego esta salida de emergencia.

Esta puerta estaba muy bien escondida, solo quienes sabían dónde estaba podían usarla. Si el ataque duraba mucho y las cosas dentro del castillo se ponían muy difíciles, esta puerta permitía salir a buscar comida, agua o incluso huir.

Imagínate a las personas del castillo usando esta salida en silencio, de noche, dejando atrás lo que no podían cargar, con la esperanza de sobrevivir y volver algún día. Esta puerta secreta muestra lo inteligentes que eran los que construyeron y vivieron en el castillo, ya que pensaban en todas las posibilidades, incluso en las más difíciles.

Dirígete al centro del patio de entrada donde verás un arco para pasar al siguiente patio. Antes de entrar por el arco, pasa al siguiente audio.

Escape Door

At the far end of this entrance courtyard, there is something that at first might not seem very important, but in reality, it was key in case of attack: a secret escape door.

Although Pedraza Castle was built to withstand attacks, the owners also considered the possibility of the enemies winning. That’s where this emergency exit came into play.

This door was very well hidden, only those who knew where it was could use it. If the attack lasted too long and things inside the castle became very difficult, this door allowed them to go out to get food, water, or even to flee.

Imagine the people in the castle using this exit quietly at night, leaving behind what they couldn’t carry, hoping to survive and return one day. This secret door shows how clever those who built and lived in the castle were, as they thought of all possibilities, even the most difficult ones.

Go to the center of the entrance courtyard where you will see an archway to the next courtyard. Before you enter through the archway, go to the next audio.

4. EL PASADIZO DEL TIEMPO

Este pasadizo es como un túnel del tiempo, pero no es ciencia ficción. Si te paras en frente podrás ver como el castillo ha ido creciendo con el tiempo y como ha ido dejando huellas de diferentes épocas en este corto recorrido.

The passageway of time

This passageway is like a tunnel through time, but it’s not science fiction. If you stand in front of it, you’ll see how the castle has grown over time and how it has left traces of different eras in this short stretch.

4A. Tres arcos

Al entrar al pasadizo, el primer arco que ves es ojival de estilo gótico, con forma puntiaguda y el siguiente es románico de medio punto, con una forma más redondeada. Esto quiere decir que el castillo era más pequeño al principio y luego fue ampliado. La primera parte es del siglo XIII, y las ampliaciones y mejoras se hicieron a finales del siglo XV.

Three Arches

As you enter the passageway, the first arch you see is Gothic, with a pointed shape, and the next one is Romanesque, with a more rounded shape. This means that the castle was smaller at first and then expanded. The first part dates back to the 13th century, and the extensions and improvements were made at the end of the 15th century.

5. Rastrillo

Casi todos los castillos tienen una puerta especial llamada rastrillo, que caía como una guillotina. En Pedraza, el rastrillo estaba en el arco románico de este pasaje. Aunque desapareció́ hace siglos, aún se ven marcas de donde estaba. Esta puerta, también conocida como hermética o peine, era esencial para la defensa de los castillos medievales. Al estar hecha de hierro y podía bajarse rápidamente para bloquear a los enemigos si atacaban por sorpresa.

Imagina esto: los enemigos atacan, y los defensores sueltan la cuerda que sostiene el rastrillo. La puerta cae de golpe, bloqueando el camino y atrapando a los atacantes en el pasadizo. Era la última barrera antes de llegar al interior del castillo, una verdadera trampa para los invasores. Incluso si los atacantes conseguían romper la puerta principal, se encontrarían atrapados en este pasadizo, teniendo que enfrentarse a los defensores.

Al salir del pasadizo y llegar al patio de armas, veras que la construcción cambia. La saetera, (las ventanas estrechas para disparar flechas), las piedras redondeadas y el suelo más bajo son señales de otra época del castillo.

Portcullis

Almost all castles have a special door called a portcullis, which would drop like a guillotine. In Pedraza, the portcullis was located in the Romanesque arch of this passage. Although it disappeared centuries ago, you can still see marks of where it was. This door, also known as a grille, was essential for the defense of medieval castles. It was made of iron and could be dropped quickly to block enemies in case of a surprise attack.

Imagine this: the enemies attack, and the defenders release the rope holding the portcullis. The door crashes down, blocking the path and trapping the attackers in the passageway. It was the last barrier before reaching the castle’s interior, a real trap for invaders. Even if the attackers managed to break through the main gate, they would find themselves stuck in this passageway, facing the defenders.

When you exit the passageway and reach the bailey, you’ll notice that the construction changes. The arrow slits (narrow windows for shooting arrows), the rounded stones, and the lower ground level are signs of another era of the castle.

6. EL PATIO DE ARMAS

Nos adentramos en el patio de armas. El patio de armas era el corazón del castillo, donde pasaba todo. Aquí́ se entrenaba a los soldados y se hacían eventos sociales. Antes era más pequeño, y había otras construcciones como habitaciones, establos y almacenes, pero todo fue destruido en un incendio.

The Bailey

We’re now in the bailey. The bailey was the heart of the castle, where everything happened. Soldiers were trained here, and social events took place. It used to be smaller, and there were other structures like rooms, stables, and storerooms, but all of them were destroyed in a fire.

6A. LOS JARDINES

Cuando Ignacio Zuloaga, un famoso pintor español que era muy conocido por sus retratos y paisajes que mostraban la vida y cultura de España, compró el castillo en 1926 estaba en ruinas, el fuego había acabado con varias partes del castillo y muchas piedras y elementos de su estructura habían desaparecido. Zuloaga lo restauró y rehabilitó las torres y el espacio entre ellas para construir su estudio y vivienda familiar. Además, convirtió́ parte del espacio en jardines. Construyó una piscina para su familia y daba clases de pintura allí́, aprovechando la luz. Hoy en día, estos jardines son perfectos para fiestas, bodas y eventos. Además, el castillo ha sido usado como escenario para series y películas medievales como Isabel, Águila Roja y la serie de terror 30 monedas de Alex de la Iglesia.

The Gardens

When Ignacio Zuloaga, a famous Spanish painter known for his portraits and landscapes that depicted Spanish life and culture, bought the castle in 1926, it was in ruins. Fire had destroyed several parts of the castle, and many stones and structural elements were missing. Zuloaga restored it, rehabilitated the towers, and used the space between them to build his studio and family residence. He also converted part of the space into gardens. He built a pool for his family and gave painting classes there, taking advantage of the light. Today, these gardens are perfect for parties, weddings, and events. The castle has also been used as a set for medieval series and films, such as Isabel, Águila Roja, and the horror series 30 Coins by Álex de la Iglesia.

6B. EL MURO

Las piedras de los muros cuentan prácticamente la historia del castillo. En el fondo norte del muro, se puede ver un levantamiento de piedra que es parte de la pared sobre la que apoyaban las vigas de madera con sus cabezales incrustados en la piedra. Esta pared se extendía paralela al muro. Esto significa que el edificio tenía tres pisos y que en el primero y segundo estaban la mayor parte de las habitaciones con grandes ventanas y banquitos laterales, para disfrutar de las vistas al bosque.

The Wall

And… how was it built?

The wall was built in the 13th century with very strong stone (though it has had to be repaired several times to keep it standing). Some of these reconstructions were carried out by the Herrera and Velasco families in the 15th and 16th centuries (remember? The two families that were very important to the castle…)

Over the years, neither bad weather nor enemy attacks managed to destroy the wall. However, if you look closely, you can see the marks of ancient projectiles, like stones from catapults, cannonballs, and shots from old weapons like muskets. If you look carefully, you can try to spot these marks on the castle’s facade.

Remember that during the War of Independence against Napoleon, French troops invaded much of Spain, and many fortified towns like Pedraza suffered damage.

Even so, projectiles were not the worst. The most significant damage the castle suffered was when it was abandoned, and locals took stones and other materials to build their own houses. It is believed that the keep lost about five meters in height, and in some parts of the wall, up to two or three meters of stone are missing.

Now head over to the cannon port that is located right in front of the entrance gate and once there, go to the next audio.

6C. El Campanario

Si miras hacia arriba, justo encima de los tres arcos que has atravesado para acceder a este patio, Aún se puede ver el arco donde colgaba una campana, que se conserva intacto y se puede ver desde lejos. Su construcción de piedra labrada superpuesta ha hecho que pueda mantenerse en el tiempo a pesar del viento y el hielo. Aunque ha pasado mucho tiempo, las cigüeñas lo usan para hacer sus nidos.

The Bell Tower

If you look up, just above the three arches that you have passed through to access this courtyard, you can still see the arch where a bell once hung, which remains intact and can be seen from afar. Its construction, with overlapping carved stones, has allowed it to withstand the weather, despite wind and ice. Although much time has passed, storks use it to build their nests.

6D. LA MAZMORRA

Aunque hay una creencia popular de que todos los castillos tenían sus mazmorras, la realidad es que lo más común era encerrar a los presos en bodegas o habitaciones aisladas ya que no

todos los castillos tenían su propia mazmorra. Sin embargo, el de Pedraza sí tiene una, y puedes visitarla. Está en el centro del patio de armas, tiene el escudo de la familia Herrera, está bajo tierra, y es oscura, fría y húmeda. Con el paso de los años y la falta de rehenes, dejó de usarse para encerrar a gente y en sus últimos años, se ha usado para guardar agua de lluvia.

The Dungeon

Although there’s a popular belief that all castles had dungeons, the reality is that it was more common to imprison people in cellars or isolated rooms since not all castles had their own dungeon. However, Pedraza Castle does have one, and you can visit it. It’s in the center of the bailey, with the Herrera family’s coat of arms, underground, dark, cold, and damp. Over the years and with fewer prisoners, it stopped being used to imprison people, and in its later years, it was used to store rainwater.

7. LAS LETRINAS

Las letrinas colgando de los muros más altos, eran un elemento común en los castillos medievales. Que, por cierto, es importante no confundirlas con los matacanes, que también son salientes de piedra que se usaban como defensa para atacar a los invasores.

La letrina de este castillo está subiendo hacia la primera torre del homenaje o torre residencial. Son como pequeños balcones con dos agujeros que permitían que cuando alguien tuviese que ir al baño, todo cayera fuera del castillo, gracias a la gravedad. Solían estar cerca de las habitaciones de los señores, y no era raro que las usaran dos personas a la vez, ya que no se daba tanta importancia a la privacidad como hoy.

¿Sabias que… en algunos castillos era importante proteger estos agujeros durante un ataque enemigo, ya que a veces intentaban entrar por ahí.?

The Latrines

The latrines hanging from the highest walls were a common feature in medieval castles. By the way, it’s important not to confuse them with machicolations, which are also stone projections used for defense, from which invaders were attacked.

The latrine in this castle is located as you climb toward the first keep, or residential tower. They are like small balconies with two holes that allowed everything to fall outside the castle, thanks to gravity. They were usually near the lords’ rooms, and it wasn’t uncommon for two people to use them at the same time, as privacy wasn’t as important as it is today.

Did you know… in some castles, it was important to protect these holes during an enemy attack, as sometimes attackers tried to enter through them?

8. IGNACIO ZULOAGA

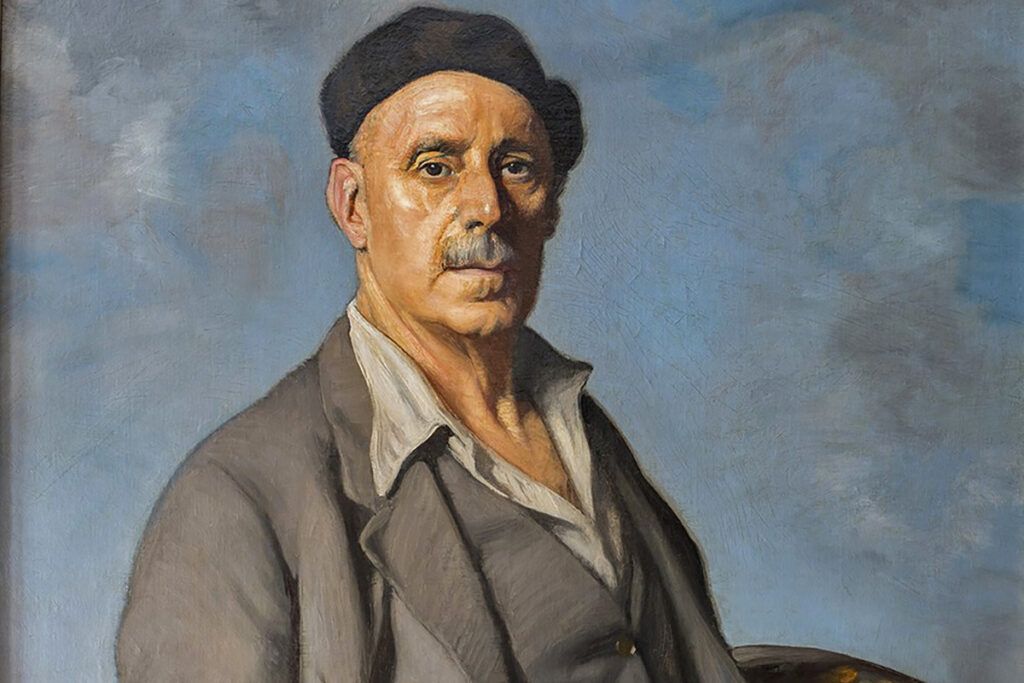

Ignacio Zuloaga nació en la localidad guipuzcoana de Eibar en 1870 y está considerado uno de los grandes pintores de España de finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX, y probablemente el artista más grande del costumbrismo español. Falleció en el año 1945 en Madrid.

Ignacio Zuloaga compró el castillo y la iglesia en 1926, salvando a Pedraza de convertirse en un pueblo abandonado. En su momento, en Pedraza había unos 1500 habitantes y cuando el pintor conoció la localidad, tan solo había 45 vecinos. Casi todas las casas de antiguos nobles y señores estaban abandonadas y en decadencia. Zuloaga rehabilitó el castillo y lo convirtió en su hogar y estudio. A Zuloaga le encantaba este lugar y decía que le hacía sentirse aislado del mundo, como en la Edad Media.

Cuando en 1925 Ignacio Zuloaga adquirió la fortaleza medieval de Pedraza lo primero que hizo fue frenar el espolio y el deterioro que estaba sufriendo.

Ignacio Zuloaga.

Ignacio Zuloaga was born in the Gipuzkoan town of Eibar in 1870 and is considered one of the great painters of Spain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and probably the greatest artist of Spanish costumbrismo. He died in 1945 in Madrid.

Ignacio Zuloaga bought the castle and the church in 1926, saving Pedraza from becoming an abandoned town. At the time, Pedraza had about 1,500 inhabitants, but when the painter discovered the town, there were only 45 residents left. Almost all the houses of the former nobles were abandoned and in decay. Zuloaga restored the castle, turning it into his home and studio. Zuloaga loved this place and said it made him feel isolated from the world, like in the Middle Ages.

When in 1925 Ignacio Zuloaga acquired the medieval fortress of Pedraza, the first thing he did was to stop the spoliation and deterioration it was suffering.

9. SALA ZULOAGA

En esta primera torre, situada en el interior, se encuentra instalada la Sala Zuloaga dedicada a homenajear al artista con la exposición de algunas réplicas de sus cuadros más conocidos, sobre todo los que se usaron en billetes de pesetas que circularon en España en el siglo XX.

El régimen de Franco tras la guerra y quedarse España aislada, necesitaba hacerse fuerte consiguiendo que famosos de la época y artistas lo apoyaran. Por eso sacaron la obra de Zuloaga en varios billetes que a la vez le rendían homenaje directamente.

Concretamente fueron cuatro los billetes españoles que contenían pinturas de Ignacio Zuloaga y que podrás ver en está sala.

ZULOAGA HALL

In this first tower, located in the interior, is installed the Zuloaga Hall dedicated to pay tribute to the artist with an exhibition of some replicas of his most famous paintings, especially those used in the banknotes that circulated in Spain in the twentieth century.

with the exhibition of some replicas of his best known paintings, especially those that were used in peseta banknotes that circulated in Spain in the twentieth century.

Franco’s regime, after the war and the isolation of Spain, needed to make itself strong by getting celebrities of the time and artists to support it. That is why Zuloaga’s work was featured on several banknotes that at the same time paid tribute to him directly.

Specifically, there were four Spanish banknotes that contained paintings by Ignacio Zuloaga, which you can see in this room.

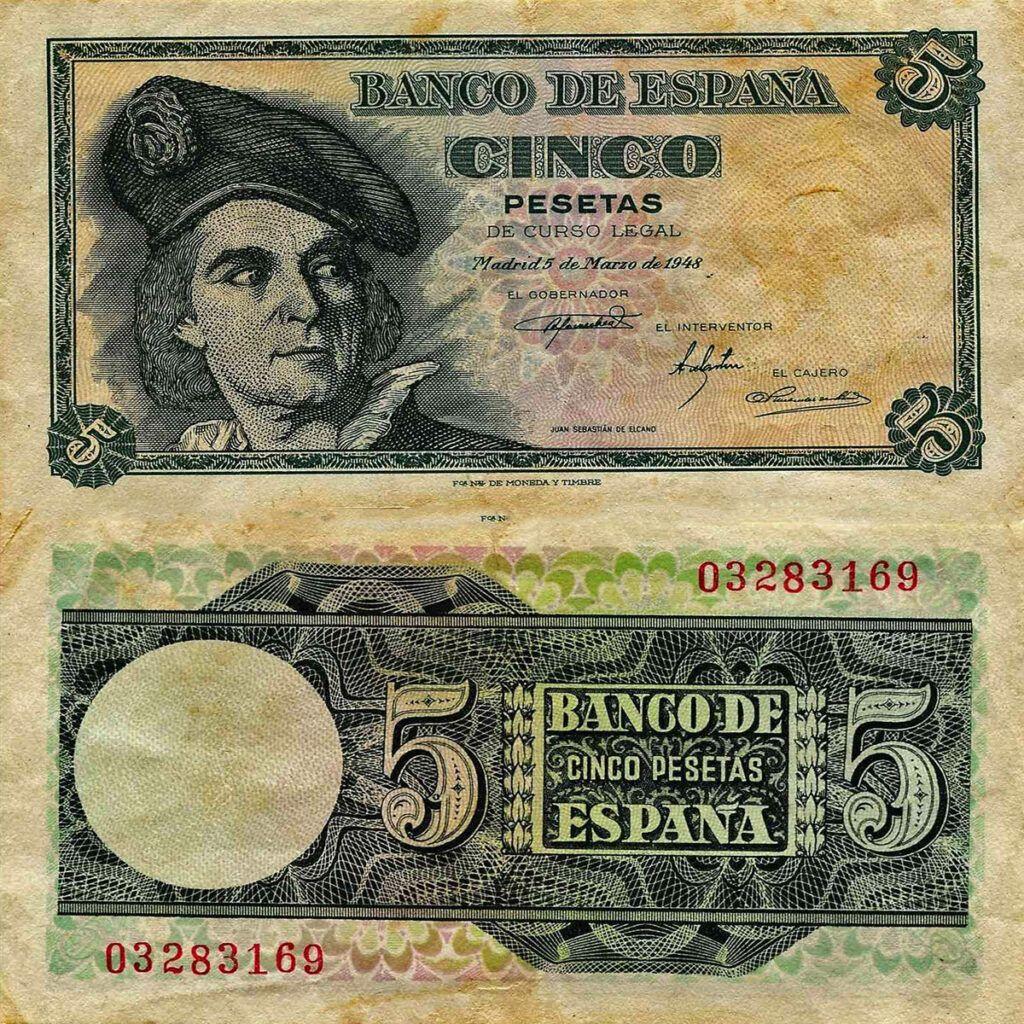

9A. Las 5 pesetas de 1948

El primero fue el de las 5 pesetas de 1948. En él aparece un retrato de Juan Sebastián Elcano, un marino de Guipúzcoa que completó la primera vuelta al mundo en 1522.

En 1921, cuatro siglos después de que lo hiciera, la Diputación de Guipúzcoa quiso celebrar el 400 aniversario con dos retratos de Juan Sebastián Elcano, así que encargó uno de ellos a Zuloaga, que en ese momento ya era un pintor reconocido y estaba viviendo en Zumaya, un pueblito muy cerca de Guetaria que es donde nació Elcano.

El problema que encontró Zuloaga es que no había ninguna referencia de cómo era el aspecto de este marinero.

¿Sabias que? … ¿El retrato que aparece en el billete no es de Juan Sebastían Elcano sino de un amigo de Zuloaga llamado Pío Gogoza Egaña? Zuloaga se imaginaba a Elcano como un vasco arrogante y esbelto. Así que buscó a un vasco de esas características que le sirviera de modelo, y lo encontró en un amigo suyo que se llamaba Pío Gogoza Egaña, un inspector municipal veterinario de Zumaya.

Este hombre era arrogante, buen trabajador y muy aficionado a la bebida. Zuloaga le propuso hacer de modelo para retratar a Elcano y dijo que sí. Imagínate!! Ver tu cara en los billetes sin ser nadie conocido!

El cuadro original se encuentra en el Palacio Provincial de Guipúzcoa desde 1921.

The 5 pesetas of 1948

The first was the 5 pesetas of 1948. On it appears a portrait of Juan Sebastián Elcano, a sailor from Guipúzcoa who completed the first round-the-world voyage in 1522.

In 1921, four centuries after he did it, the Diputación de Guipúzcoa wanted to celebrate the 400th anniversary with two portraits of Juan Sebastián Elcano, so it commissioned one of them to Zuloaga, who at that time was already a recognized painter and was living in Zumaya, a small town very close to Guetaria, where Elcano was born.

The problem that Zuloaga encountered was that there was no reference of what this sailor looked like.

Did you know that … the portrait that appears on the banknote is not of Juan Sebastían Elcano but of a friend of Zuloaga’s named Pío Gogoza Egaña? Zuloaga imagined Elcano as an arrogant and slender Basque. So he looked for a Basque with those characteristics to serve him as a model, and he found him in a friend of his named Pío Gogoza Egaña, a municipal veterinary inspector from Zumaya.

This man was arrogant, a good worker and very fond of drinking. Zuloaga proposed him to be the model to portray Elcano and he said yes. Imagine! Seeing your face on the banknotes without being anyone you know!

The original painting has been in the Provincial Palace of Guipuzcoa since 1921.

today in the Zuloaga Museum?

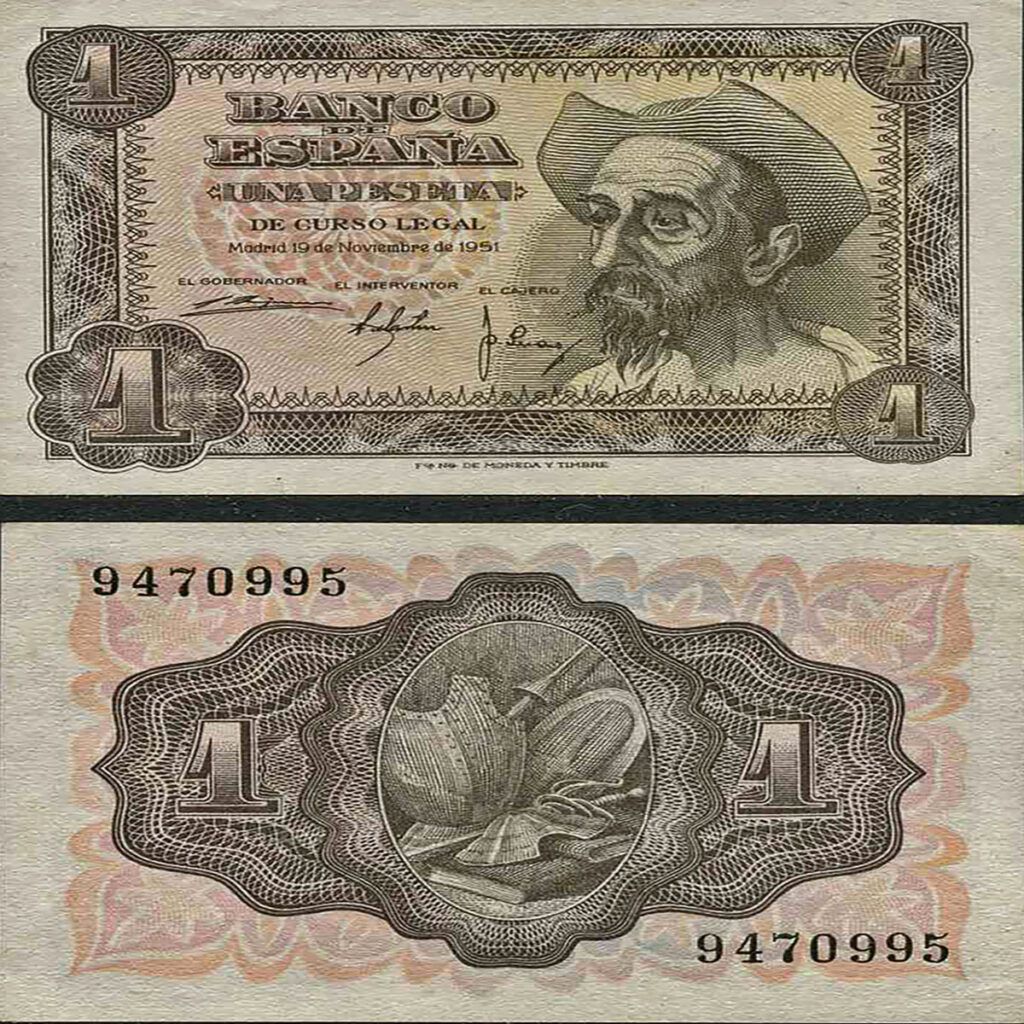

9B. 1 peseta de 1951 Historia de una amistad

Después, en 1951, vino el billete de una peseta. Un billete bastante conocido y el más usado!! Se hicieron 191 millones de ejemplares. Fue la penúltima peseta que se emitió en papel.

En el anverso del billete aparece un retrato de don Quijote de la Mancha, y en el reverso vemos elementos representativos del ingenioso hidalgo: yelmo, lanza, escudo, bacía y libros. dibujos que también hizo Zuloaga.

¿Sabías que estos dibujos los hizo Zuloaga como encargo de una escenografía para una ópera?

Te cuento: nos remontamos a 1918. Esta es la bonita historia de tres amigos. Winnaretta Singer, Manuel de Falla y Zuloaga. Te pongo en situación:

¿Quién era Winnaretta Singer?, ¿a que te suena el apellido “Singer”?.

1 peseta of 1951 History of a friendship

Then, in 1951, came the one peseta bill. A very well known and the most used banknote! 191 million copies were made. It was the penultimate peseta to be issued on paper.

On the front of the banknote there is a portrait of Don Quixote de la Mancha, and on the back we see representative elements of the ingenious nobleman: helmet, lance, shield, coat of arms and books. These drawings were also made by Zuloaga.

Did you know that these drawings were made by Zuloaga as a commission for a set design for an opera?

Let me tell you: we go back to 1918. This is the beautiful story of three friends. Winnaretta Singer, Manuel de Falla and Zuloaga. Let me put you in the picture:

Who was Winnaretta Singer, does the surname “Singer” ring a bell?

9C. WINNARETTA SINGER

Winnaretta Singer nació en Nueva York en 1865, heredera de la famosísima empresa de máquinas de coser Singer Corporation, Asi que te puedes imaginar, era multimillonaria.

Se casó muy joven con el Príncipe Louis de Scey-Montvéliard, porque Winnaretta buscaba por encima de todo, la libertad que solo podría darle un matrimonio concertado. Sin embargo, todos sabían que era lesbiana, cosa que ella no ocultaba en absoluto, y la Iglesia Católica decidió anular su matrimonio.

Pero Winnaretta se casó de nuevo y muy rápido, con el príncipe Edmond de Polignac, ¿y por que se caso siendo lesbiana?. Pues muy fácil, porque Edmod también era homosexual y 30 años mayor que ella. Por supuesto, no tuvieron hijos, pero eran muy buenos amigos y juntos consiguieron traer todo el arte y la cultura del mundo a la ciudad de París. Ella se convirtió en una gran mecenas, algo asi como un patrocinador de la época, e invirtió toda su fortuna en ayudar a artistas y a subvencionar obras. Asi es como conoció a los mejores músicos de su tiempo, entre ellos, Manuel de Falla.

¿sabías que Winnaretta tuvo relaciones también con muchas mujeres casadas?. Es Famoso el día en que el esposo de una de sus amantes gritaba a la puerta de su mansión “Si eres la mitad de hombre que crees que eres, vente afuera y pelea conmigo”.

WINNARETTA SINGER

Winnaretta Singer was born in New York in 1865, heiress of the famous sewing machine company Singer Corporation, so you can imagine, she was a multimillionaire.

She married Prince Louis de Scey-Montvéliard at a very young age, because Winnaretta sought above all else the freedom that only an arranged marriage could give her. However, everyone knew that she was a lesbian, which she did not hide at all, and the Catholic Church decided to annul her marriage.

But Winnaretta married again and very quickly, with prince Edmond de Polignac, and why did she marry being a lesbian? Very easy, because Edmond was also homosexual and 30 years older than her. Of course, they had no children, but they were very good friends and together they managed to bring all the art and culture of the world to the city of Paris. She became a great patron, something like a patron of the time, and invested all her fortune in helping artists and subsidizing works. This is how she met the best musicians of her time, among them Manuel de Falla.

Did you know that Winnaretta also had relations with many married women? Famously, the husband of one of her lovers shouted at the door of her mansion “If you are half the man you think you are, come outside and fight with me”.

9D. MANUEL DE FALLA - EL RETABLO DE MAESE PEDRO

Winnaretta llamó a Manuel de Falla y le propuso componer una ópera de cámara. Falla compuso la ópera, basada en el capítulo 26 de la segunda parte del Quijote. Consistía en una escena en la que unos titiriteros están representando una trama y Don Quijote, que como ya sabemos confundía la ficción con la realidad, desenvaina su espada y se pone a dar sablazos contra el teatro y los títeres.

Seguro que el título de está obra te suena, se llamó “El retablo de Maese Pedro”. El día del estreno en París, el 25 de junio de 1923, las expectativas eran muy altas, pero el éxito fue arrollador, y pronto superó en repercusión los éxitos que Falla había obtenido con cualquier otra obra. Se representó en muchas ciudades como Bristol, Sevilla, Barcelona, Bilbao, Nueva York, Amsterdam, Berlín y un largo etc.

¿sabías que Falla tardó más de 5 años en escribirla? La princesa no estaba muy contenta con la tardanza, pero el mismo Falla le confesó que lo que para el había comenzado como “un mero divertimento”, se había convertido, palabras textuales, “entre todas mis obras, aquella en la que mayor iluisión he puesto”.

¿y que tiene que ver Zuloaga en todo esto?

MANUEL DE FALLA. EL RETABLO DE MAESE PEDRO.

Winnaretta called Manuel de Falla and proposed to compose a chamber opera. Falla composed the opera, based on chapter 26 of the second part of Don Quixote. It consisted of a scene in which some puppeteers are representing a plot and Don Quixote, who as we already know confused fiction with reality, unsheathes his sword and starts beating the theater and the puppets.

Surely the title of this play is familiar to you, it was called “El retablo de Maese Pedro”. On the day of the premiere in Paris, June 25, 1923, expectations were very high, but the success was overwhelming, and soon surpassed in impact the successes that Falla had obtained with any other work. It was performed in many cities such as Bristol, Seville, Barcelona, Bilbao, New York, Amsterdam, Berlin and many more.

Did you know that it took Falla more than 5 years to write it? The princess was not very happy with the delay, but Falla himself confessed to her that what for him had begun as “a mere amusement”, had become, in his own words, “among all my works, the one in which I have put the greatest illusion”.

And what has Zuloaga to do with all this?

9E. FALLA Y ZULOAGA

Manuel de Falla e Ignacio Zuloaga se admiraban mutuamente como artistas. Su amistad se inicia en 1913 cuando el compositor le pide a Zuloaga ayuda y consejos para la puesta en escena de “la vida breve”. Después de esto se hicieron intimos amigos y esta relación de amistad les anima a trabajar juntos en un gran proyecto en el que la música y la escena, contaban con la dirección de ambos artistas. Falla se ocupó de la música y Zuloaga de la escenografía. Ya te puedes imaginar cual fue este gran proyecto, pues si, El retablo de maese Pedro”.

Pues, Zuloaga hizo un montón de bocetos que luego se quedó su familia, y que más tarde recopiló la Fundación Zuloaga. Concretamente el dibujo de don Quijote que aparece con la famosa vacía de barbero es el que aparece en el billete de peseta de 1951.

De esta forma en el billete de 1 peseta, se hacía un triple homenaje a artistas españoles: Por un lado a Cervantes, por otro a Zuloaga y de manera indirecta a Falla, autor de la obra musical. Y todo gracias a Winnareta Singer.

FALLA AND ZULOAGA

Manuel de Falla and Ignacio Zuloaga admired each other as artists. Their friendship began in 1913 when the composer asked Zuloaga for help and advice for the staging of “La vida breve”. After this they became close friends and this friendship encouraged them to work together on a great project in which both artists directed the music and the stage. Falla was in charge of the music and Zuloaga of the scenography. You can imagine what this great project was, yes, El retablo de maese Pedro”.

Well, Zuloaga made a lot of sketches that were later kept by his family, and later compiled by the Zuloaga Foundation. Concretely, the drawing of Don Quixote that appears with the famous barber’s empty is the one that appears on the 1951 peseta banknote.

In this way, the 1 peseta bill paid a triple homage to Spanish artists: on the one hand to Cervantes, on the other hand to Zuloaga and indirectly to Falla, author of the musical work. And all thanks to Winnareta Singer.

9F. 500 pesetas de 1954

El billete de las 500 pesetas de 1954 es más un homenaje directo a Zuloaga. No sólo a su obra, sino a la misma persona.

En el anverso del billete sale su autorretrato que se hizo en 1942 cuando tenía 72 años. De hecho, es el último de los autorretratos que pintó y el más conocido de todos. Se llama “Autorretrato con fondo azul” y los críticos dicen que es magnífico.

En el cuadro completo aparece con sus pinceles de pintor, con chaleco, camisa, chaqueta y una boina, dando una imagen natural del pintor campechano, cercano… vamos de pueblo, pero a la vez digno y con mirada intensa.

Este autorretrato también apareció en los sellos de dos pesetas de 1971. Y a día de hoy, la obra original se conserva en la Fundación Zuloaga.

En el reverso del billete, se ve otra obra de Zuloaga que pintó en 1932: “Paisaje claro de Toledo”.

Para que te hagas una idea, Toledo no era una ciudad cualquiera para Zuloaga, la pintó hasta seis veces entre 1924 y 1938. En esta obra, se ve el puente de San Martín, y en general una ciudad luminosa y serena, y no tan dramática como en otros paisajes de Toledo que hizo.

No es raro que se eligiera un paisaje castellano para este billete en vez de uno vasco, que es de donde era, porque el pintor también era un amante de Castilla, algo que tenía en común con otros artistas de la generación del 98.

En general, estos artistas veían en Castilla la esencia más profunda de España y Zuloaga siempre tuvo un vínculo muy fuerte con esa zona y sobre todo con Toledo.

500 pesetas of 1954

The 500 pesetas bill of 1954 is more a direct homage to Zuloaga. Not only to his work, but to the person himself.

On the front of the banknote is his self-portrait that he painted in 1942 when he was 72 years old. In fact, it is the last of the self-portraits he painted and the best known of all. It is called “Self-portrait with blue background” and critics say it is magnificent.

In the complete painting he appears with his painter’s brushes, with a vest, shirt, jacket and beret, giving a natural image of the country painter, close to the people, but at the same time dignified and with an intense look.

This self-portrait also appeared on the 1971 two-peseta stamps. And to this day, the original work is kept in the Zuloaga Foundation.

On the back of the banknote, you can see another work by Zuloaga that he painted in 1932: “Paisaje claro de Toledo” (Clear Landscape of Toledo).

To give you an idea, Toledo was not just any city for Zuloaga, he painted it up to six times between 1924 and 1938. In this work, you can see the bridge of San Martín, and in general a luminous and serene city, and not as dramatic as in other landscapes of Toledo that he painted.

It is not strange that a Castilian landscape was chosen for this bill instead of a Basque one, which is where he was from, because the painter was also a lover of Castile, something he had in common with other artists of the generation of ’98.

In general, these artists saw in Castile the deepest essence of Spain and Zuloaga always had a very strong bond with that area and especially with Toledo.

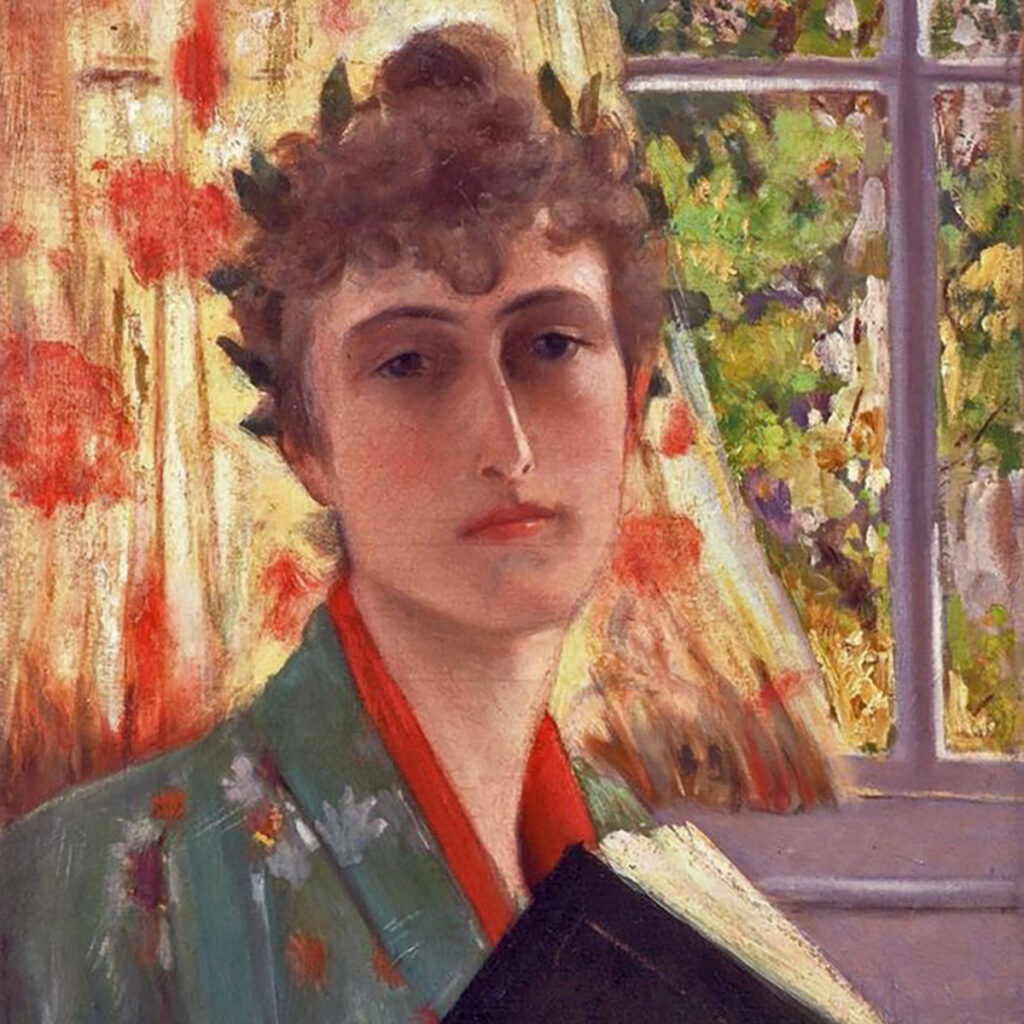

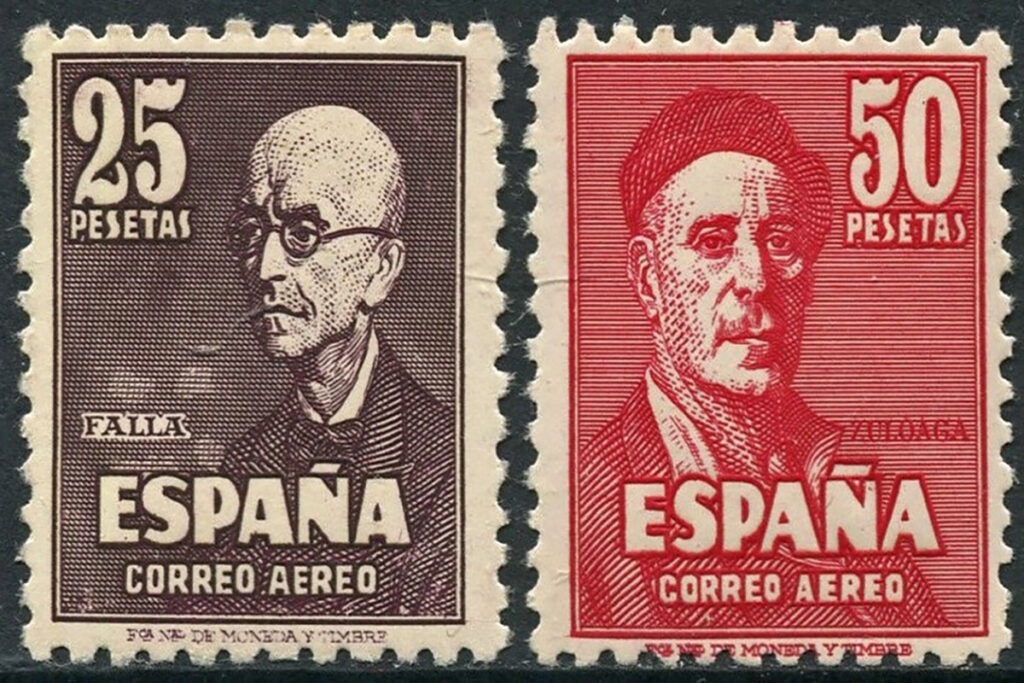

9G. 100 pesetas de 1970

El de 100 pesetas de 1970 es el último billete en el que aparece la obra de Zuloaga. Este billete es un homenaje total a su gran amigo Manuel de Falla.

En el anverso aparece un retrato suyo y en el reverso una imagen de la Alhambra de Granada. ciudad que se vincula mucho con Falla porque a pesar de que no nació allí, sí que vivió en Granada durante mucho tiempo.

Como te hemos contado antes, la amistad entre Manuel de Falla y Zuloaga es muy conocida y se ha escrito mucho sobre ella, se han hecho exposiciones y hasta existe el hashtag #zuloagayfalla.

Hay más de doscientas cartas que lo demuestran.

En general, colaboraron mucho el uno con el otro en diferentes trabajos. La última vez que se vieron fue en 1932 en Zumaya, en la casa de Zuloaga. Invitaron a Falla a la inauguración del Museo de San Telmo en San Sebastián y este aprovechó para pasar unos días en casa de Zuloaga. Y fue allí donde le hizo el retrato tan conocido.

En esa obra se le ve como una persona madura, mayor, y medio enfermo. También aparece Granada. Así que este fue el retrato que se utilizó para representar a Falla en ese billete de 1970, que aparte de homenajear a Falla, también hace un homenaje a la amistad que tenía con Zuloaga.

El original pertenece a la colección particular de la familia Zuloaga y de vez en cuando se exhibe en exposiciones. Aunque también se ha utilizado en varios sellos españoles varias veces.

Al final Manuel de Falla emigró a Argentina en 1939, donde murió el 14 de noviembre de 1946 de tuberculosis, a los 69 años. Murió casi justo un año después de que falleciera Zuloaga en Madrid, el 31 de octubre de 1945.

100 pesetas of 1970

The 1970 100 pesetas is the last banknote on which Zuloaga’s work appears. This banknote is a total homage to his great friend Manuel de Falla.

On the front there is a portrait of him and on the back an image of the Alhambra in Granada, a city that is closely linked to Falla because although he was not born there, he did live in Granada for a long time.

As we have told you before, the friendship between Manuel de Falla and Zuloaga is well known and much has been written about it, exhibitions have been made and there is even the hashtag #zuloagayfalla.

There are more than two hundred letters that prove it.

In general, they collaborated a lot with each other in different works. The last time they saw each other was in 1932 in Zumaya, in Zuloaga’s house. Falla was invited to the inauguration of the San Telmo Museum in San Sebastian and he took the opportunity to spend a few days at Zuloaga’s house. It was there that he painted the well-known portrait of him.

In that work he is seen as a mature, elderly, and half sick person. Granada also appears. So this was the portrait that was used to represent Falla in this 1970 banknote, which apart from paying homage to Falla, also pays homage to the friendship he had with Zuloaga.

The original belongs to the private collection of the Zuloaga family and is occasionally exhibited in exhibitions. It has also been used on several Spanish stamps several times.

Manuel de Falla finally emigrated to Argentina in 1939, where he died on November 14, 1946 of tuberculosis, at the age of 69. He died almost a year after Zuloaga died in Madrid, on October 31, 1945.

10. LA TORRE DEL HOMENAJE

En un castillo medieval, la torre del homenaje es la más alta y fuerte, y siempre está en la parte más difícil de atacar. Cuando Ignacio Zuloaga compró el castillo, arregló esta torre, que estaba en ruinas, y la convirtió́ en su estudio de pintura y vivienda.

La segunda torre, que es más pequeña, pudo haber sido también torre del homenaje antes de las ampliaciones del siglo XV que hicieron los Herrera.

The Keep

In a medieval castle, the keep is the tallest and strongest tower, and it is always located in the hardest part to attack. When Ignacio Zuloaga bought the castle, he restored this tower, which was in ruins, and turned it into his painting studio and residence.

The second, smaller tower may also have been the keep before the 15th-century expansions made by the Herrera family. It is now used to house the Ignacio Zuloaga Museum.

11. LAS HABITACIONES

El castillo tiene seis habitaciones que la familia Zuloaga construyó entre los restos de las dos torres para vivir. Cada una es diferente, y de hecho, puedes hospedarte en ellas porque están equipadas con baño moderno y climatización. ¿Te imaginas dormir en un castillo medieval con las comodidades de hoy?

The Rooms

The castle has six rooms that the Zuloaga family built between the remains of the two towers to live in. Each one is different, and in fact, you can stay in them because they are equipped with modern bathrooms and climate control. Can you imagine sleeping in a medieval castle with today’s comforts?

12. EL ESTUDIO

La sala principal de la torre del homenaje es un gran salón de piedra que Zuloaga usaba como su estudio de pintura. Tenía dos camas antiguas con dosel donde descansaba cuando lo necesitaba y una gran chimenea para mantenerse caliente en los días fríos.

The Studio

The main room of the keep is a large stone hall that Zuloaga used as his painting studio. It had two old canopy beds where he rested when needed and a large fireplace to keep warm on cold days.

13. Sala Francisco I Rey de Francia.

Este salón está dedicado a los hijos del Rey de Francia Francisco I.

En 1529, dos hijos del rey de Francia, Francisco I, estuvieron retenidos en la torre del castillo de Pedraza. Esto fue para asegurarse de que su padre cumpliera el acuerdo que hizo con el emperador Carlos V después de ser capturado en la batalla de Pavía en 1525. Francisco I prometió entregar tierras a España a cambio de su libertad, pero como garantía, dejó a sus hijos, Enrique (de 7 años) y Carlos de Orleans (de 4 años), como rehenes.

Los niños estuvieron prisioneros en Pedraza hasta 1530, cuando fueron liberados tras un nuevo acuerdo entre Francia y España. Durante su tiempo en el castillo, se cuenta que vivieron en condiciones difíciles: mal vestidos, en una habitación oscura y fría, con solo unos perritos para entretenerse. Esta historia ha pasado de generación en generación, y se dice que, como venganza, las tropas de Napoleón quemaron el castillo siglos después.

Room Francis I King of France.

This room is dedicated to the children of the King of France Francis I.

In 1529, two sons of the King of France, Francis I, were held in the tower of Pedraza Castle. This was to ensure that their father kept the agreement he made with Emperor Charles V after being captured at the Battle of Pavia in 1525. Francis I had promised to give up lands to Spain in exchange for his freedom, but as a guarantee, he left his sons, Henry (7 years old) and Charles of Orleans (4 years old), as hostages.

The children were imprisoned in Pedraza until 1530 when they were released following a new agreement between France and Spain. It is said that they lived in difficult conditions during their time in the castle: poorly dressed, in a dark, cold room, with only a few puppies to entertain them. This story has been passed down through generations, and it is said that, as revenge, Napoleon’s troops burned the castle centuries later.

14. PATIO DE LA IGLESIA

El patio que da al sur era el jardín de la iglesia. Antes había una pequeña capilla que ya no existe, solo queda la pila bautismal, que se puede ver junto al muro. Este sitio también era uno de los favoritos de Zuloaga, donde le gustaba pintar porque la luz y la temperatura eran

perfectas. También, en el centro del patio hay un pozo muy profundo que todavía da agua, aunque está tapado por seguridad.

The church courtyard

The courtyard facing south was the garden of the church. There used to be a small chapel here, but it no longer exists. Only the baptismal font remains, which can be seen next to the wall. This spot was also one of Zuloaga’s favorites, where he loved to paint because the light and temperature were perfect. In the center of the courtyard, there is also a very deep well that still provides water, though it is covered for safety.

14A. UN LUGAR ESPECIAL

La zona donde está Pedraza siempre ha sido aprovechada por diferentes pueblos, desde los más antiguos. Se cree que ha estado habitada desde la Edad del Bronce o incluso antes (¡osea hace unos 4.000 años o más!). Pueblos como los vacceos y los arévacos, que vivían antes de los romanos, construían sus aldeas en colinas para protegerse mejor.

Más tarde, durante la Reconquista (que recuerda es la época en la que los reinos cristianos lucharon para recuperar tierras controladas por los árabes), se construyó́ una fortaleza en Pedraza para controlar la zona. Luego, por el año 1200 (ósea hace unos 800 años), se empezó a construir el castillo de Pedraza sobre las ruinas de esas antiguas fortificaciones.

¿Sabías que?…el pintor Ignacio Zuloaga compró este castillo por 13.000 pesetas que son 78€?

A Special Place

The area where Pedraza is located has always been used by different peoples, from the most ancient times. It’s believed that it has been inhabited since the Bronze Age or even earlier (around 4,000 years ago or more!). Peoples like the Vaccaei and the Arevaci, who lived before the Romans, built their villages on hills to better protect themselves.

Later, during the Reconquista (the period when Christian kingdoms fought to take back lands controlled by the Arabs), a fortress was built in Pedraza to control the area. Then, around the year 1200 (about 800 years ago), the Pedraza castle began to be built over the ruins of those ancient fortifications.

Did you know?… The painter Ignacio Zuloaga bought this castle for 13,000 pesetas, which is equivalent to 78 euros!

13,000 pesetas, which is equivalent to 78 euros!

15. Sala “Los amantes Elvira y Roberto” La leyenda del castillo

Como buen castillo medieval, el de Pedraza también tiene su leyenda y sus fantasmas. Se cuenta que un noble llamado don Sancho se encaprichó de una plebeya muy guapa que se llamaba Elvira, con la que se casó ejerciendo su derecho feudal. Pero… ella estaba enamorada de Roberto, un joven labrador que, desconsolado por la boda, se metió en un convento. Vamos, que se hizo monje.

Pasados los años, tras la muerte del capellán del castillo (osea el sacerdote encargado de realizar los servicios religiosos en el castillo) escogieron al antiguo labrador para que fuera a ocupar su puesto. Y por su parte Sancho tuvo que irse a la guerra para ayudar con la defensa de Castilla de la invasión de los almohades.

Elvira y Roberto se reencontraron y volvió a surgir el amor. Cuando don Sancho se enteró de la infidelidad, decidió castigar a Roberto y durante la celebración de una cena ordenó colocarle una corona de púas incandescentes, lo que hizo que Roberto muriese en el momento.

Doña Elvira, destrozada, corrió a sus aposentos a encerrarse, prendió fuego a la torre y se clavó una daga en el corazón. La leyenda dice que, en algunas noches de verano, se pueden ver las almas de los amantes caminando bajo un resplandor de fuego.

En la sala encontrarás un libro mágico. En Homenaje a Elvira y Roberto, estos dos amantes que vivieron su amor en secreto dentro de estos muros, nos gustaría que escribieras en este libro, quién es tu amor secreto para compartirlo con los protagonistas de nuestra leyenda. seguramente eso hará que no se sientan tan solos e incomprendidos, y quien sabe… igual esto hace que sus almas se liberen algún día.

Room “The lovers Elvira and Roberto”. The Legend of the Castle

Like any good medieval castle, Pedraza also has its legends and ghosts. It is said that a nobleman named Don Sancho became infatuated with a beautiful commoner named Elvira, whom he married by exercising his feudal right. But… she was in love with Roberto, a young farmer who, heartbroken by the wedding, entered a monastery and became a monk.

Years later, after the death of the castle chaplain (the priest responsible for religious services in the castle), the former farmer was chosen to take his place. Meanwhile, Sancho had to go to war to help defend Castile from the Almohad invasion.

Elvira and Roberto reunited, and their love rekindled. When Don Sancho learned of the infidelity, he decided to punish Roberto. During a dinner celebration, he ordered a crown of burning thorns to be placed on Roberto’s head, killing him instantly.

Doña Elvira, devastated, ran to her chambers, locked herself in, set the tower on fire, and stabbed herself in the heart with a dagger. Legend says that, on some summer nights, the souls of the lovers can be seen walking under a fiery glow.

In the room you will find a magical book. In homage to Elvira and Roberto, these two lovers who lived their love in secret within these walls, we would like you to write in this book, who is your secret love to share it with the protagonists of our legend. Surely this will make them not feel so alone and misunderstood, and who knows… maybe this will free their souls someday.

16. EL MIRADOR

Lo que más llama la atención de este patio es el mirador que Zuloaga hizo construir deshaciendo parte de la muralla. Desde ahí, se pueden ver los bosques y unas increíbles puestas de sol sobre la sierra de Guadarrama. Hoy en día, este mirador es el lugar donde muchas parejas deciden casarse, porque es un lugar mágico para comenzar una nueva vida juntos.

The Lookout

The most striking feature of this courtyard is the lookout that Zuloaga had built by dismantling part of the wall. From there, you can see the forests and enjoy incredible sunsets over the Sierra de Guadarrama. Today, this lookout is where many couples choose to get married, as it is a magical place to begin a new life together.

16A. EL TERRENO Y SUS ALREDEDORES

Pedraza está en lo alto de una meseta, a 1060 metros de altura, así que te puedes imaginar lo increíbles que son las vistas. El terreno es bastante plano, con algunas pequeñas colinas que forman parte de las montañas de la Sierra de Guadarrama. Alrededor del castillo, los campos suelen usarse para la agricultura y la cría de animales, lo que le da un aspecto rústico y muy tradicional.

Desde el castillo puedes sentir el fresquito del río Cega, que pasa cerca de Pedraza. Este río, que es parte del río Duero, ha ayudado a que los valles que están cerca sean fértiles.

La vegetación alrededor de Pedraza es la típica de la meseta castellana. Hay muchos árboles como encinas viejas, pinos, enebros, cipreses y sabinas que llenan el paisaje. También se ven campos con cultivos de cereal y prados. Este entorno natural no solo hace que el Castillo de Pedraza se vea aún más bonito, sino que también transmite mucha tranquilidad.

Puedes dirigirte hacia la salida para escuchar la siguiente historia sobre la puerta del castillo. El portón.

The Land and Its Surroundings

Pedraza is located on top of a plateau, 1,060 meters above sea level, so you can imagine how amazing the views are. The land is quite flat, with some small hills that are part of the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains. Around the castle, the fields are mostly used for agriculture and livestock, giving it a rustic and very traditional look.

From the castle, you can feel the cool breeze from the Cega River, which flows near Pedraza. This river, which is part of the Duero River, has helped make the nearby valleys fertile.

The vegetation around Pedraza is typical of the Castilian plateau. There are many trees like old holm oaks, pines, junipers, cypresses, and savins that fill the landscape. You can also see fields with cereal crops and meadows. This natural environment not only makes Pedraza Castle even more beautiful but also brings a lot of peace.

You can head towards the exit to hear the following story about the castle gate. The gate.

17. EL PORTÓN

Pocos castillos conservan su puerta original en tan buen estado como la del castillo de Pedraza. Tiene más de 500 años, pero sigue en pie gracias a varios factores. Primero, está hecha de álamo negro, una madera muy resistente, llena de nudos y casi inmune a la polilla cuando se seca bien. Esta madera crece cerca de los ríos Cega y Eresma, que están por la zona.

Los pinchos de hierro que cubren la puerta se hicieron a mano uno por uno. Servían para amortiguar los golpes de los enemigos y daban al castillo una imagen de fuerza. Están asegurados a una placa de metal en la parte trasera para que no pudieran ser arrancados. Aunque algunos han desaparecido, sobre todo en la parte de abajo, todavía conserva muchos.

La llave de la puerta es la original y también es impresionante. Está hecha de una sola pieza de metal y pesa unos dos kilos. Aunque lleva 500 años funcionando, su mecanismo es muy simple: la propia llave empuja el pasador. Hoy en día hay una copia moderna por seguridad, pero sigue siendo un símbolo del castillo.

Gate

Few castles still have their original door in such good condition as the one at Pedraza Castle. It’s over 500 years old but still standing, thanks to several factors. First, it’s made of black poplar, a very strong wood, full of knots, and almost immune to woodworms when it dries well. This wood grows near the Cega and Eresma rivers, which are in the area.

The iron spikes covering the door were handmade, one by one. They served to cushion enemy blows and gave the castle an image of strength. They are secured to a metal plate on the back so they couldn’t be ripped out. Although some are missing, especially at the bottom, many are still there.

The door’s key is the original and is also impressive. It’s made from a single piece of metal and weighs about two kilos. Even though it’s been working for 500 years, its mechanism is very simple: the key itself pushes the bolt. Nowadays, there is a modern copy for security, but it remains a symbol of the castle.

17A. ESCUDO

Una vez fuera del castillo, sobre el portón principal, en la fachada, se puede ver el escudo de los Fernández de Velasco tallado en piedra. Recuerda que esta familia era muy importante y que fue dueña del castillo y del pueblo de Pedraza. Además, mejoró el castillo, dándole un aspecto más elegante y lujoso.

Pero… ¿Qué representan los escudos y cuál es su historia? Mira:

Todo comenzó con un matrimonio que tuvo lugar en 1472, donde empezó una larga lista de los Velasco, duques de Frías, como señores de Pedraza durante tres siglos.

Doña Blanca Herrera, la única hija heredera de la familia Herrera (los dueños anteriores a los Velasco), se casó con don Bernardino Fernández de Velasco.

Gracias a este matrimonio, el castillo pasó a ser de la familia Fernández de Velasco durante tres siglos. Bernardino fue un hombre muy importante, ya que los Reyes Católicos le dieron el título de Duque de Frías en 1492 y fue el II Condestable de Castilla, lo que significa que era el jefe militar más importante después del rey.

Seguimos: Bernardino tuvo una hija que se llamaba Ana, pero cuando él murió, el castillo no fue para ella, si no para su hermano Íñigo Fernández de Velasco. Así que… te puedes imaginar: En 1512 hubo una pelea entre el hermano de Bernardino, don Íñigo, y el marido de Ana, don Álvaro Pimentel Pacheco, porque discutían sobre quién debía quedarse con el castillo. Se cree que Bernardino murió repentinamente, tal vez envenenado, sin que le diese tiempo a dejar arreglada su herencia.

Se cree que pudo haber sido envenenado por una dama de la reina Germana de Foix, segunda mujer de Fernando el Católico porque se llevaban muy mal, pero esa es otra historia.

Al final, Don Íñigo heredó el castillo, y luego su hijo, Pedro Fernández de Velasco, lo tomó. Los escudos de esta familia se pueden ver en varios lugares del pueblo, como en la entrada y en la antigua cárcel, una torre medieval del siglo XII. Estos escudos eran una forma de mostrar el poder de los nobles sobre el lugar hasta que en 1812 las Cortes de Cádiz abolieron el régimen feudal.

Además, cada escudo tiene un significado. Por ejemplo, el de los Fernández de Velasco muestra su riqueza, poder y la protección de la familia con ocho piezas de oro que representan generosidad, y siete figuras que simbolizan nobleza y protección. Al pasear por Pedraza, puedes encontrar más escudos de otras familias importantes que vivieron allí, como los Astorga, Osuna, Salcedo, y muchas más.

Sabias que… el régimen feudal era una forma de organización de la sociedad en la Edad Media?. En este sistema, el rey le daba tierras a los nobles (osea a los ricos) a cambio de lealtad y ayuda militar. Los nobles, a su vez, dejaban que los campesinos vivieran y trabajaran en sus tierras, pero los campesinos tenían que dar una parte de lo que producían al noble y no eran completamente libres. A cambio, los nobles ofrecían protección y seguridad.

Coat of Arms

Once outside the castle, Above the main gate, on the facade, you can see the coat of arms of the Fernández de Velasco family, carved in stone. Remember that this family was very important and was the owner of the castle and the town of Pedraza. They also improved the castle, giving it a more elegant and luxurious appearance.

But… what do the coats of arms represent, and what’s their history? Look:

It all started with a marriage that took place in 1472, which began a long line of Velascos, Dukes of Frías, as lords of Pedraza for three centuries. Doña Blanca Herrera, the only heir of the Herrera family (the owners before the Velascos), married Don Bernardino Fernández de Velasco.

Thanks to this marriage, the castle belonged to the Fernández de Velasco family for three centuries. Bernardino was a very important man, as the Catholic Monarchs gave him the title of Duke of Frías in 1492, and he was the second Constable of Castile, meaning he was the highest military leader after the king.

Let’s continue: Bernardino had a daughter named Ana, but when he died, the castle didn’t go to her but to her brother, Íñigo Fernández de Velasco. So… you can imagine: in 1512, there was a fight between Bernardino’s brother, Don Íñigo, and Ana’s husband, Don Álvaro Pimentel Pacheco, because they argued over who should inherit the castle. It’s believed that Bernardino died suddenly, perhaps poisoned, without having time to sort out his inheritance.

It’s thought he may have been poisoned by a lady-in-waiting of Queen Germana de Foix, the second wife of Ferdinand the Catholic, because they didn’t get along, but that’s another story.

In the end, Don Íñigo inherited the castle, and then his son, Pedro Fernández de Velasco, took it. The coats of arms of this family can be seen in several places around the town, such as at the entrance and at the old prison, a medieval tower from the 12th century. These coats of arms were a way to show the nobles’ power over the area until 1812, when the Cortes of Cádiz abolished the feudal system.

Did you know?… The feudal system was a way of organizing society in the Middle Ages. In this system, the king gave land to nobles (the rich) in exchange for loyalty and military aid. The nobles, in turn, let peasants live and work on their land, but the peasants had to give a portion of what they produced to the noble and were not completely free. In exchange, the nobles offered protection and security.

Moreover, each coat of arms has a meaning. For example, the Fernández de Velasco coat of arms shows their wealth, power, and family protection with eight gold pieces representing generosity and seven figures symbolizing nobility and protection. As you walk through Pedraza, you can find more coats of arms from other important families that lived there, such as the Astorga, Osuna, Salcedo, and many others.

17B. El puente levadizo

Con el paso del tiempo y con la llegada de nuevas tecnologías, los puentes levadizos dejaron de ser útiles en los castillos y poco a poco fueron desapareciendo. No se sabe exactamente cuándo se quitó el puente del castillo de Pedraza, pero seguro que puedes imaginarte como se abría el foso y como cruzaban los nobles y sus mensajeros a caballo.

Sobre el portón todavía se pueden ver algunos restos de las poleas que levantaban el puente con cadenas. Cuando el puente estaba bajado, descansaba sobre unas vigas, que fueron reemplazadas por el muro de granito con bolas que aun puedes ver. Este puente levadizo hacía que el castillo fuese impenetrable.

Una vez que has cruzado el puente levadizo, verás más adelante a la izquierda una iglesia en ruinas. Es la Iglesia de Santa María.

Drawbridge

As time passed and new technologies arrived, drawbridges became less useful in castles, and little by little, they disappeared. It’s not known exactly when the drawbridge at Pedraza Castle was removed, but you can certainly imagine how the moat opened and how nobles and their messengers crossed it on horseback.

Above the gate, you can still see some remnants of the pulleys that lifted the bridge with chains. When the bridge was lowered, it rested on beams, which were replaced by the granite wall with balls that you can still see today. This drawbridge made the castle impenetrable.

Once you have crossed the drawbridge, you will see ahead on the left a church in ruins. It is the Church of Santa Maria.

17C. La iglesia de Santa María

Con la compra del castillo y sus alrededores, Zuloaga también se quedó la antigua iglesia de Santa María que estaba totalmente en ruinas, como continua a dia de hoy. Puedes visitar lo que queda de ella caminando por la Calle de la Calzada hacia el pueblo. La iglesia fue construida entre los siglos XI y XII, y aunque no queda mucho en pie, aun se puede apreciar su ábside, la ventana de medio punto con arquivolta y sus capiteles, propios de la artesanía de la época. Aunque quedan pocas piedras en pie, su historia y espíritu todavía se sienten, recordando tiempos llenos de vida y devoción.

The Church of Santa María

When Zuloaga bought the castle and its surroundings, he also acquired the old Church of Santa María, which was in complete ruins, as it remains today. You can visit what’s left of it by walking along Calle de la Calzada toward the town. The church was built between the 11th and 12th centuries, and although not much remains, you can still see its apse, the semicircular window with an archivolt, and its capitals, typical of the craftsmanship of the time. Although few stones are still standing, its history and spirit can still be felt, reminding us of times filled with life and devotion.

17D. Lugares de Interés y caminos

Para entrar al castillo y al pueblo, como lo hacían nuestros antepasados, hay que pasar por una sola puerta: La Puerta de la Villa, que formaba parte del sistema de defensa antiguo.

Desde allí, puedes andar por calles empedradas que mantienen el estilo medieval y cerca del castillo también hay senderos antiguos para explorar la naturaleza.

Un lugar interesante que está cerca es la Iglesia de San Juan Bautista, que está en la plaza principal de Pedraza y tiene un aire histórico, al igual que el castillo. Un poco más lejos está el Parque Natural de las Hoces del Río Duratón, perfecto para los fanáticos del senderismo y para ver paisajes increíbles, como los cañones que ha formado el río. ¡Es un lugar que no te puedes perder!

Points of Interest and Paths

To enter the castle and the town, just like our ancestors did, you have to pass through a single gate: La Puerta de la Villa, which was part of the old defense system.

From there, you can walk along cobblestone streets that maintain the medieval style, and near the castle, there are also old trails to explore the nature.

An interesting place nearby is the Church of San Juan Bautista, located in the main square of Pedraza, and it has a historical air, just like the castle. A little further away is the Natural Park of the Hoces del Río Duratón, perfect for hiking fans and for seeing incredible landscapes, like the canyons formed by the river. It’s a place you can’t miss!

17E. Despedida

Y aquí termina la visita al Castillo de Pedraza, esperamos que hayas disfrutado de está audio-guía y que su contenido te haya parecido interesante. Te damos las gracias por tu visita y ¡ojalá vuelvas pronto

¡Adiós!

Farewell

And here ends the visit to Pedraza Castle, we hope you have enjoyed this audio-guide and that you have found its content interesting. We thank you for your visit and hope you come back soon! Goodbye!